A Returned Peace Corps Volunteer's memories and views of his years in upcountry Sierra Leone from 1968 to 1970

Monday, June 18, 2012

Tuesday, June 12, 2012

Bockarie Su Gande - Master Mende Carver

Wednesday, June 6, 2012

Where are you now, Pa Sam?

|

| Pa Sam at his farmhouse near Vaama Nongowa c. 1969 photo © by Chad Finer |

In the village of Vaama, a village about 4 to 6 miles from Kenema, Pa Sam and his wife Massa lived. He was friends and perhaps family of the Garloughs, a family that befriended us when we moved to Kenema in August 1968. Although a very generous man, he was more businesslike then friendly. It was at sometime in my first year in Kenema that our paths crossed. Massa made regular visits to Kenema to visit the Garloughs and to shop in Kenema. I best remember her for her wonderful smile and friendliness. Although she only spoke Mende (I was quite limited in my Mende conversation), we could communicate to some degree. I remember also that during Bondo activity she would play the segburre, a woman's instrument used to accompany song. Pa Sam, on the other hand, rarely came through town and was more likely to be out there in Vaama working on his farm. Diminutive, wiry, yet strong, he could work all day in the hot sun and never seem to tire. His hands were weathered from all the farm labor. With cutlass in hand he would brush his farm in preparation for the planting of upland rice. On the hills by Vaama he would plant acres of rice, see to it that birds were driven from eating the ripening rice kernels, and when harvest time arrived, he and Massa would pick the rice, bag it, store some for their own use, and give the rest away to family and needy friends. There was a time when I went to help him as he prepared his farm for planting. I remember it because, unlike Pa Sam who had hands of leather, my hands were far from used to brushing with a cutlass. It was in the village of Tokpombu that I had commissioned a local blacksmith to make me two cutlasses. He crafted them out of car springs and made the handle out of car tires. My brushing skills were minimal, yet on that day Pa Sam and I worked side by side getting the land ready. However, I was to last a short time. My hand blistered terribly and though Pa Sam admirably labored the entire day, I had to give up as my hand became painful and useless. Much to his credit, he ignored my plight as I apologized for not being able to keep on. By mid-day I headed home to nurse my wounds. A lesson learned.

I have my doubts that the village of Vaama, a tiny settlement of maybe ten houses, survived the war. And what of Pa Sam and his wife Massa? Such noble folks, I wonder where they are now and whether they are alive.

|

|

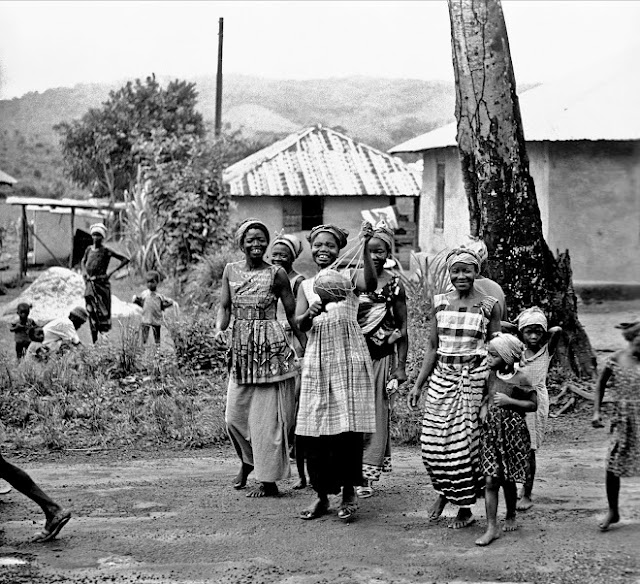

Massa plays the segburreh - taken on Dama Road in Kenema c. 1969 Massa was married to Pa Sam -

taken across the road from our house - photo © by Chad Finer |

Thursday, May 31, 2012

Rice on the Upland

Tuesday, May 29, 2012

Diamonds

|

a small, raw diamond of industrial quality - this was shown to me as I traveled on the bush road from our house

to the village of Vaama Nongowa c. 1969 - photo © by Chad Finer

|

Although this rich supply of diamonds in Sierra Leone had some potential to help the country's economy - most of the time it did not. Too many times this industry led to corruption of officials and to a smuggling undercurrent being driven by both the artificial pricing of diamonds in Europe and America which kept the value of diamonds and very high levels, and being driven by greed. This industry, which had great potential to support many in country ventures such as education and other infrastructure projects unfortunately was more likely to lead to men abandoning their villages and families, and heading off to find their fortunes in these wild areas where crime was rampant, where there was little in the way of social structures, and where less than a handful ever met with success. Many times these diamond digging areas turned into wastelands where lawlessness and chaos seemed more likely. And who really benefited? Those in power. Those across the seas in Europe and America. Europeans if you will. The average Sierra Leone citizen saw little if anything. And as the corruption became more prominent - greed became overwhelming. Diamond selling became a means by the few to become rich. It was diamonds that was later to become the means by which some could finance armaments that had never before been seen in Sierra Leone. Automatic weaponry financed by the blood diamonds snuck its way into the Sierra Leone persona and charismatic, quixotic, and evil men drove this charge, bent on control, drunk on power,and with their selling of diamonds, able to finance the horror that became an 11 year battle to steal a country. They bought this sophisticated weaponry and handed it to a youth that was ready to be bad. They kidnapped children and made them (coerced them if you will) into child soldiers. They created camps where women were used as sex slaves - and this was all done as a war policy. And they made the children kill their own. These war crimes included the maiming and killing of its own citizens as a policy of horror and terror. This all had never been seen in Sierra Leone before. From 1991 to 2002 this horror - this civil war - sat down on a poor country. Folks left in droves to escape the killing and the maiming. As rebels and others roamed the country creating havoc, those who could ran away. For a decade there was little schooling. For ten years the social fabric of the country was in stress and challenge. And the scars of this horror - have left a disheartening memory on the psyche of this proud country.

Saturday, May 26, 2012

Pa Maju Bah - Al Hajji and Fula Section Chief - Kenema, Sierra Leone

Tuesday, May 15, 2012

Talent

|

| Pa Foday Koroma, village chief and weaver of country cloth - Bitema Nongowa c. 1969 |

Thursday, May 3, 2012

Forests and Villages

Monday, April 30, 2012

Sunday, April 15, 2012

Travel to Koindu

all photos © by Chad Finer

Travel to the international market and to Koindu from where we lived (Kenema) took a full day of travel by public transport. At some point early in our second year we

Travel to the international market and to Koindu from where we lived (Kenema) took a full day of travel by public transport. At some point early in our second year weMonday, April 9, 2012

Climate as I saw it

The climate in Sierra Leone took some getting used to. Days could get hot with maximum temperatures hovering around 100ºF during the dry season. On many days the humidity could be stifling. Clothes on the line might not dry, and bed sheets felt moist when time came to sleep. In our first days I think it was the humidity that got to us most. Those days were often interspersed with both sun and clouds and rain. The rain would come off and on during those early rain season days and come in sheets. Clouds would be low in the sky, and often there would be thunder and lightening. Sometimes there would be heavy winds and heavy, heavy rain. So – our first weeks in Sierra Leone, in July 1968 I noticed the humidity and try as we might to adjust to it, there seemed nothing that we could do. We dressed in light cotton clothes and by mid morning, as sweat pored off, our clothes would be soaked and in need of change. If there was rain, it might feel a slight bit cooler, but again it was the moisture in the air that seemed to be the challenge. Early on we bought large umbrellas that we carried everywhere. Rains could come quickly and without warning, and could delay your walking about. Rain season, as it was called, began sometime in late March or early April and lasted until October. During that period, the area got between 150 and 200 inches of rain. Some days rain seemed to last all day but more likely was a day in which there might be sun intermittently mixed with periods of downpour. In Kenema, there was slightly less rain and humidity than in Freetown but this difference was minor.

So our first few months in country required adjustments with the climate being one of a number of challenges. However, as time went on we clearly started to figure it all out. The heat became increasingly tolerable. We figured out how to deal with the intense sun, and we learned how to adjust to the humidity. And – I suspect – there was a change in our physiology as well. In those first few weeks, my clothes would be drenched by mid morning and with just minimal activity walking about. And after our first few months in Kenema, I could walk from our house to downtown Kenema and back, umbrella in hand, and barely sweat at all. Something clearly changed within us. During the October to March dry season the sun during the day could get quite harsh but when we headed downtown to shop, our umbrellas would protect us not from rains, which never came during dry season, but from the sun. And as the dry season continued on in February and March, the days would get increasingly humid, but again rain did not fall. On a trip down to Kenema from our home, a distance of more than a mile, the heat could be terrific if we chose midday to head out, and with it, the humidity could be brutal. But dry season nights and early mornings could be downright comfortable. In December, dry winds off the Sahara called the Harmattan, were cooling and dusty. The air on some days might be tan tinged in color as dust off the Sahara would be blown toward our area. But there were times when we were comfortable – we even joked about being cold. Our neighbors found those mornings quite cool and they would dress with extra clothing. For us, those days would be the most pleasant.

Saturday, April 7, 2012

A Volunteer in Sierra Leone

Saturday, March 31, 2012

More About my teaching (at HRSS)

Friday, March 23, 2012

Kenema

Monday, March 12, 2012

Country Cloth

c. 1970

c. 1970small country cloth bed spread or lappa (5 ft 6 inches x 7 ft 6 inches)

traditional Mende men's country cloth robe

traditional Mende men's country cloth robe a large country cloth made by Pa Brimah Daru in 1970 (6ft 6 x 10 ft 6)In Kenema, from time to time we used to run into Pa Brimah, who was a master weaver of country cloth. In Kenema, he might meet us in town as we were shopping and try to sell us place mats for our table. With us he was successful – and sold us a number of place mats that we used while in Kenema and also brought these homes for our use as well as for gifts for our family. I was well-aware of the value of cotton country cloths.

a large country cloth made by Pa Brimah Daru in 1970 (6ft 6 x 10 ft 6)In Kenema, from time to time we used to run into Pa Brimah, who was a master weaver of country cloth. In Kenema, he might meet us in town as we were shopping and try to sell us place mats for our table. With us he was successful – and sold us a number of place mats that we used while in Kenema and also brought these homes for our use as well as for gifts for our family. I was well-aware of the value of cotton country cloths.Tuesday, March 6, 2012

Peace Corps Films from my era

These are from my era as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Sierra Leone - Enjoy!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xjI9Hy5xzP0

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cGsBgtJLsMg

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SiIte-1tgJA&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lFCXbXO4OA0

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KsGlxGGnqr0

Saturday, March 3, 2012

Masanga Leprasarium

Tuesday, February 21, 2012

Hokey "Kpokpoi"

Thursday, February 16, 2012

summit - March 1970

summit 1969

summit 1969 summit of Bintimani (6381ft) - March 1969 - © - the large tubular structure behind me marks the summit (highest point)

summit of Bintimani (6381ft) - March 1969 - © - the large tubular structure behind me marks the summit (highest point)Thursday, January 26, 2012

Merriman at Gbenderoo

© by CF

© by CF

Monday, January 23, 2012

#77 Pademba Road - Freetown, Sierra Leone

77 Pademba Rd - Freetown, Sierra Leone

77 Pademba Rd - Freetown, Sierra Leone